The mechanized nature of warfare during the Second World War tested the limits of human endurance. Physical exhaustion had always concerned military commanders, but technological advances in the 1930s and 1940s created new possibilities for conducting operations across great distances, at any time of the day, including night warfare. Mechanized vehicles in the army, navy and air force could operate indefinitely, so long as there was fuel. Advancements in radio communications and radar imaging allowed combat operations to continue throughout the night. The ‘blitzkrieg’ style of warfare required near-superhuman efforts to equip rapidly advancing armies with munitions and supplies. The weakest link in this unrelenting style of warfare was the soldier, who found less time than ever for sleep and rejuvenation. Concerns about lack of sleep were not unwarranted. As J.D. Ratcliff said of combat in the South Pacific: “In a great many instances the difference between sleepiness and alertness is the difference between life and death. A man who dozes off in a jungle foxhole may never wake up again.” It is therefore understandable, in light of the unprecedented human exertion required by modern warfare, that military commanders sought a solution to the problem of combat fatigue. The military looked to psychiatry for a solution; they found an answer in amphetamine.

The mechanized nature of warfare during the Second World War tested the limits of human endurance. Physical exhaustion had always concerned military commanders, but technological advances in the 1930s and 1940s created new possibilities for conducting operations across great distances, at any time of the day, including night warfare. Mechanized vehicles in the army, navy and air force could operate indefinitely, so long as there was fuel. Advancements in radio communications and radar imaging allowed combat operations to continue throughout the night. The ‘blitzkrieg’ style of warfare required near-superhuman efforts to equip rapidly advancing armies with munitions and supplies. The weakest link in this unrelenting style of warfare was the soldier, who found less time than ever for sleep and rejuvenation. Concerns about lack of sleep were not unwarranted. As J.D. Ratcliff said of combat in the South Pacific: “In a great many instances the difference between sleepiness and alertness is the difference between life and death. A man who dozes off in a jungle foxhole may never wake up again.” It is therefore understandable, in light of the unprecedented human exertion required by modern warfare, that military commanders sought a solution to the problem of combat fatigue. The military looked to psychiatry for a solution; they found an answer in amphetamine.

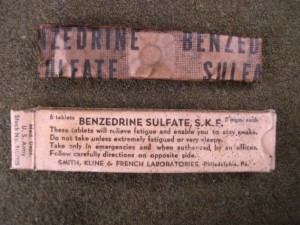

Psychiatrists of the 1920s and early 1930s discovered that chemicals could mediate brain activity, and that adrenaline, secreted naturally by the adrenal gland, was responsible for exciting the nervous system. It was believed that if adrenaline could be synthesized, it would be possible to shift brain activity into an “active, wakeful direction” whenever necessary The pharmaceutical company Smith, Kline and French (SKF) synthesized adrenaline in the form of amphetamine, which SKF patented as Benzedrine in 1932. SKF sponsored clinical trials across the country to find psychiatric applications for their new drug. It was discovered that Benzedrine could be highly effective at offsetting some of the negative symptoms of neurasthenic depression (also called ‘chronic exhaustion’), although the stimulant worsened those with anxiety disorders.

Benzedrine soon found an audience beyond the halls of psychiatry and neurology: in the school halls, work places, and households of the United States. The press sensationalized its use among students, businessmen and “housewives bored with the monotony of their unexciting lives.” The reason for Benzedrine’s popularity was due to its mood-altering effects – the very reason why Benzedrine effectively treated depression was because it produced feelings of euphoria, increased confidence, energy, and initiative. Benzedrine tablets gained the nickname ‘pep pills’ or ‘wakey-wakey pills’ in the popular press. The recreational use of Benzedrine was a problem for Smith, Kline and French, which wanted to portray its product as a legitimate pharmaceutical used in the treatment of mild neuroses like depression, narcolepsy, and fatigue. When war broke out, Benzedrine’s claim to combating fatigue promised a possible solution to the military’s age-old problem of battle exhaustion.

The British War Office discovered that between April and June 1940, at the height of the German blitzkrieg across France and the Low Countries, the Wehrmacht had consumed 35 million 3mg tablets of their own synthesized adrenaline, methamphetamine, which was marketed by a German pharmaceutical company under the name “Pervitin.” The Allies assumed that stimulants had played an important role in Germany’s military success, and Britain and the U.S. responded with their own field tests on the effects of amphetamines on soldiers’ performance.

The British War Office discovered that between April and June 1940, at the height of the German blitzkrieg across France and the Low Countries, the Wehrmacht had consumed 35 million 3mg tablets of their own synthesized adrenaline, methamphetamine, which was marketed by a German pharmaceutical company under the name “Pervitin.” The Allies assumed that stimulants had played an important role in Germany’s military success, and Britain and the U.S. responded with their own field tests on the effects of amphetamines on soldiers’ performance.

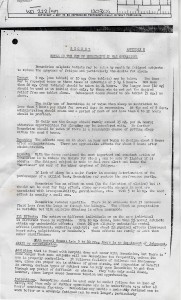

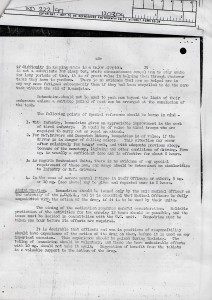

The LMH Archives contain records of British instructions on the use of Benzedrine in war operations. The instructions recommend that soldiers should ingest 5mg-10mg of Benzedrine sulphate every five to six hours, not exceeding 20mg per day, issued at the discretion of the unit medical officer when sleep was severely limited for several days. While Benzedrine was noted for its positive effect on alertness, the instructions caution that Benzedrine should not be used for its euphoric effects, since “changes in mood are associated with irresponsibility, garrulousness, etc….” Benzedrine’s ability to “relieve feelings of dullness and inadequacy” made it susceptible to abuse. Instead, the instructions recommended Benzedrine for the Infantry when exhausted troops were required to engage in work or combat, and to transport drivers and dispatch riders who needed to overcome the dangerous effect of “monotony, lighting, and other conditions of driving.” However, much like the public’s discovery of Benzedrine’s mood-altering properties, military commanders were aware of Benzedrine’s ability to increase confidence, aggression and ‘morale’ among soldiers.

Roland Winfield of the Royal Air Force was studying the effects of Benzedrine on long-range Bomber Command missions when the bomber pilot he was observing suddenly plunged his aircraft below the cover of clouds, into heavy anti-aircraft fire, in order to “press home the attack.” The pilot scored a direct hit. Winfield recommended Benzedrine for every RAF mission, for the “determination” and “aggression” that it imparted. By early 1942, Smith, Kline and French was supplying large quantities of Benzedrine to the RAF. Likewise, a British war memorandum in 1943 titled A Guide to the Preservation of Life at Sea after Shipwreck suggested that shipwrecked sailors use Benzedrine to “lessen feelings of fatigue and exhaustion, promote alertness, raise the spirits, and prolong the will to ‘hang on and live’.” That same year the Army Supply Service provided commanders with packets of six Benzedrine ‘pep pills’ for each of their soldiers. U.S. marines relied on Benzedrine during the invasion of Tarawa in November 1943, and paratroopers used the stimulant during the rigorous D-Day landings in June 1944.

Estimates of Allied consumption of amphetamines during the Second World War range from $870,000 in sales of Benzedrine Sulphate in 1943, to a staggering 72 million tablets supplied to Great Britain (and about the same amount to the United States Armed Forces) throughout the war. Although the Allies had enthusiastically adopted stimulants, the Germans largely abandoned methamphetamine by 1941, with German officials reclassifying Pervitin as a “dangerously addictive narcotic.” They weren’t wrong: there was evidence that abuse of amphetamines produced “restlessness, tremors, insomnia, talkativeness and irritability…Confusion, assaultiveness, hallucinations, delirium, panic states and suicidal or homicidal tendencies have also been observed,” according to a 1941 pharmacology textbook. However, despite the harmful side effects associated with amphetamine abuse, there is little evidence that Benzedrine impairment was responsible for any major wartime disasters.

Estimates of Allied consumption of amphetamines during the Second World War range from $870,000 in sales of Benzedrine Sulphate in 1943, to a staggering 72 million tablets supplied to Great Britain (and about the same amount to the United States Armed Forces) throughout the war. Although the Allies had enthusiastically adopted stimulants, the Germans largely abandoned methamphetamine by 1941, with German officials reclassifying Pervitin as a “dangerously addictive narcotic.” They weren’t wrong: there was evidence that abuse of amphetamines produced “restlessness, tremors, insomnia, talkativeness and irritability…Confusion, assaultiveness, hallucinations, delirium, panic states and suicidal or homicidal tendencies have also been observed,” according to a 1941 pharmacology textbook. However, despite the harmful side effects associated with amphetamine abuse, there is little evidence that Benzedrine impairment was responsible for any major wartime disasters.

—

Bibliography

Bett, W.R. “Benzedrine Sulphate in Clinical Medicine: A Survey of the Literature.” Post-Graduate Medical Journal, 22(250) (August, 1946): pp. 205-218. Accessed at http://europepmc.org/backend/ptpmcrender.fcgi?accid=PMC2478360&blobtype=pdf

Derickson, Alan. “’No Such Thing as a Night’s Sleep’: The Embattled Sleep of American Fighting Men from World War II to the Present.” Journal of Social History, Vol 47, No. 1 (Fall 2013): pp. 1-26.

N.A. “Secret – Notes on the Use of Benzedrine in War Operations, Appendix E.” (LMH Archives, WO 222/97, 120304).

Rasmussen, Nicolas. “Making the First Anti-Depressant: Amphetamine in American Medicine, 1929-1950.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Vol. 61, No. 3, (July 2006): pp.288-323.

Rasmussen, Nicolas. “Medical Science and the Military: The Allies’ Use of Amphetamine during World War II.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 42, No. 2 (Autumn 2011): pp. 205-233.

Very interesting article. I’m hoping my own work on the use of Benzedrine Sulphate in the RAF is published in article form before the end of the year. Will post a link when it is available.

Best,

James

Dr James Pugh

Centre for War Studies

University of Birmingham, UK