In the decades prior to the outbreak of the First World War, weapons technology underwent an upgrade. The introduction of machine guns and quick-fire artillery significantly changed the dynamics of waging war. Despite the lethality of the new firepower, however, a strong belief in the bayonet as an essential component for victory remained in Commonwealth military doctrine throughout the Great War. As described in The Organization of Bayonet Fighting and Physical Training in Battalion C.E.F. 1916, the bayonet remained effective in trench warfare as a weapon to remove the enemy who had been driven underground to hide from artillery fire. Bayonets were considered by some to be more effective as psychological than physical weapons. Facing a bayonet charge was a terrifying experience and often resulted in the opponent’s surrender. In the words of on one Canadian soldier: “[W]hen we hit one German with a bayonet, five fall down.”

In the decades prior to the outbreak of the First World War, weapons technology underwent an upgrade. The introduction of machine guns and quick-fire artillery significantly changed the dynamics of waging war. Despite the lethality of the new firepower, however, a strong belief in the bayonet as an essential component for victory remained in Commonwealth military doctrine throughout the Great War. As described in The Organization of Bayonet Fighting and Physical Training in Battalion C.E.F. 1916, the bayonet remained effective in trench warfare as a weapon to remove the enemy who had been driven underground to hide from artillery fire. Bayonets were considered by some to be more effective as psychological than physical weapons. Facing a bayonet charge was a terrifying experience and often resulted in the opponent’s surrender. In the words of on one Canadian soldier: “[W]hen we hit one German with a bayonet, five fall down.”

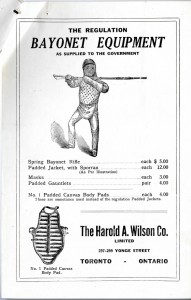

Due to the importance given to ‘cold steel’ on the battlefield, bayonet fighting remained a significant aspect of a soldier’s training. Each platoon (comprising of roughly 20-30 troops) was to have a certified instructor in charge of Bayonet Fighting and Physical Training. These instructors were chosen from among the NCOs of a unit and were required to take a 21-day course, upon the completion of which they were awarded a “cross swords badge” and paid extra for their time spent training the men of their platoon. Recruits were meant to undergo bayonet exercises for two hours each day for their first three months of basic training, and then thirty minutes each day for the remainder of their time spent as a soldier. This training generally consisted of ramming specially made spring-loaded bayonet training rifles into stuffed sacks, although padded suits were also available for trainers to don and present a live target.

Historians have debated over the use of bayonets during the war. Efforts to identify the number of casualties caused by bayonet wounds have produced statistics that question the prevalence of bayonet use in action. Paul Hodges posits that bayonets might have been responsible for as little as 1-5 per cent of deaths during the war. Since hand-to-hand combat largely took place in tight quarters of the trenches, knives, clubs, and grenades were often preferred over a bayonet fixed to a rifle. Others historians disagree. Tim Cook, for example, has argued that the soldiers’ choice to fix bayonets before every engagement speaks to an overwhelming respect for the weapon itself. Furthermore, operation reports tell us that, even though bullets and artillery caused the vast majority of casualties, successful offensive operations were generally decided by ‘cold steel’. Trenches were essential for survival, but because of the bayonet they could be dangerous as well.

Historians have debated over the use of bayonets during the war. Efforts to identify the number of casualties caused by bayonet wounds have produced statistics that question the prevalence of bayonet use in action. Paul Hodges posits that bayonets might have been responsible for as little as 1-5 per cent of deaths during the war. Since hand-to-hand combat largely took place in tight quarters of the trenches, knives, clubs, and grenades were often preferred over a bayonet fixed to a rifle. Others historians disagree. Tim Cook, for example, has argued that the soldiers’ choice to fix bayonets before every engagement speaks to an overwhelming respect for the weapon itself. Furthermore, operation reports tell us that, even though bullets and artillery caused the vast majority of casualties, successful offensive operations were generally decided by ‘cold steel’. Trenches were essential for survival, but because of the bayonet they could be dangerous as well.

Notes

Cook, Tim. At the Sharp End: Canadians Fighting the Great War, 1914-1916. Toronto: Viking Canada, 2007.

Hodges, Paul. “They Don’t Like it Up ‘Em!’: Bayonet Fetishization in the British Army During the First World War,” Journal or War and Culture Studies (2008), Vol. 1:2 pp. 123-128. Accessed September 21, 2014.

—

Ben Toews is currently a Master’s student in the Department of History at Wilfrid Laurier University, as well as a research assistant at LMH Archive.

Do you have a source for the Harold A. Wilson ad? We have a Wilson fencing musket in the City of Toronto’s artifact collection.