Ronnie Shephard’s career in operational research stretched from the Second World War to the 1990s. During this time he worked for many different government, corporate, and educational institutions, from the wartime Army Operational Research Group to the Royal Military College of Science to subsidiaries of BAE Systems.

Ronnie Shephard (center), then working for the Defence Operational Research Establishment, is briefed by members of the RAC Logistics Department in 1966. (The RAConteur Vol. II No. II, June 1 1966) Photo courtesy Gene Visco.

A great deal of Shephard’s work was designed to inform the military procurement process, where industry, government and military authorities oversee the development and delivery of goods to the armed forces, from personal equipment and small arms to tanks, trucks, aircraft and ships.

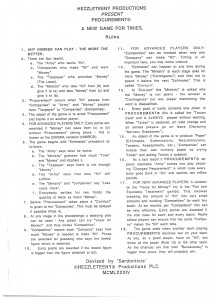

Not surprisingly, he was no stranger to the strange world of bureaucracy. Among Shephard’s papers is a rulebook for a fictional board game called Hezzleteeny Productions Present Procurement® A New Game for Tinies (ie children).

Military procurement is a notoriously twisted world, one that Procurement® lampoons exquisitely. Take rules 3 & 4, for example:

3. “Procurement” occurs when “Kit” passes from “Companies” to “Army” and “Money” passes from “Taxpayer” to “Companies” (Sometimes).

4. The object of the game is to avoid “Procurement” and blame it on another player.

Canadians are familiar with the world of procurement from such debacles as the over 30 year saga to find a replacement for our Sea King helicopters and the disastrous, $3 billion-plus acquisition of three used submarines from the Royal Navy, to say nothing of the ongoing controversy over replacing the RCAF’s ageing fleet of CF-18 fighters.

In the United States, the Pentagon has refined ‘Procurement’ to an art form. The development and procurement of the Bradley Fighting Vehicle was so perfectly mishandled that it gave rise to the popular book and later movie The Pentagon Wars. The US Marines’ effort to replace their amphibious assault vehicle dragged for 15 years and cost $3 billion before it was axed.

Hezzleteeny Productions Present Procurement® A New Game for Tinies, from The Ronnie Shephard Fonds, Laurier Military History Archive.

Even projects that deliver can cost astronomically more than originally estimated. Pentagon projects like the Zumwalt class destroyer demonstrate that the rules of Procurement® are as relevant as ever:

6. f. “Everybody settles for two thirds the [“Kit”] at twice as much “Money.”

In all, the rules make for an ingeniously self-defeating gaming experience. Besides avoiding “Procurement,” the only point of it is to amass “Paper.” With this in mind, the game eventually “ends when another team playing Procurement® declares war on your team,” and the whole thing devolves into literally throwing paper.

May the biggest bureaucracy win.

To read Procurement®, click the thumbnail, right.