Starting with this entry, the LMH Archive will begin publishing a series of blog posts featuring select items from our holdings. This item is from the Ronnie Shephard Fonds.

By Matt Baker

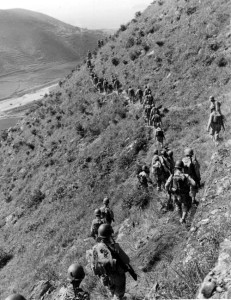

In ground combat, the outcome of battle often depends on some of the most banal and unglamorous tools: the infantryman’s weapons and equipment. The study ‘Use of Infantry Weapons and Equipment in Korea’ examines both through detailed observations on soldiers’ kit and the nature of small arms use. In 1952 the US Army-affiliated Operations Research Office interviewed 636 enlisted soldiers attached to various units to collect the raw data which, supplemented by interviews with officers, allowed them “to determine how the infantryman used his assigned weapons in Korea, what difficulties he experienced either because of the characteristics of the weapon itself or because he was insufficiently or improperly trained, and what load of clothing and equipment he carried.”

The question of small arms use in combat is a controversial one, largely due to S.L.A. Marshall’s 1947 book Men Against Fire. In it, he claimed at best only one quarter of GIs actually fired their weapons in combat, though that number increased to 55 percent by the time he published 1952’s Commentary on Infantry and Weapons in Korea 1950–51. In terms of the Marshall debate, the ORO report provides the sort of hard data that historians have so criticised Marshall for neglecting to gather. It also largely agrees with his findings on the ratio of fire in Korea, as Kelly C. Jordan has pointed out.

However, the ORO report has much more to offer than simply another perspective on Marshall. In addition to its analysis it includes a quantitative breakdown of soldiers’ equipment, the frequency and nature of small arms use, weapons maintenance, ammunition, and the role of small unit support weapons in both offensive and defensive actions. It also includes figures on the rate of soldiers’ actual participation in fighting with both experienced and inexperienced squads. In sum, it offers an intimate look at the interaction of the infantryman and his weapons and equipment in the Korean War.

Armies have long grappled with the soldier’s load and how to balance protection, mobility, and firepower. Not surprisingly, there is often a great disparity between what an army issues and what men actually carry into battle, and the interviews conducted by the ORO reveal an obsession among GIs with lightening their load. Despite the harsh climate, a large percentage of men discarded greatcoats, cold weather shoepacs, and combat packs, along with any spare clothing besides socks. The reason for this was to carry more ammunition; US troops could hardly carry enough clips for their M1 rifles.

The issue of ammunition was so important to GIs that many requested more bayonet training so they might be more prepared in the event of running out of ammo in the middle of an engagement. Interviewed soldiers identified further deficiencies in their training, and wished for instruction on multiple infantry weapons rather than just their assigned weapon, as well as more training in night time and defensive actions. Interestingly, while Marshall claimed he was responsible for improvements in US Army training regimes between WWII and Korea, an alarming number of GIs signalled they were unhappy with their weapons training, which focused too heavily on offensive fire. Said one GI: “You’re never taught in basic that you can be shot at, too; you always just take a hill and are never run off it.”

important to GIs that many requested more bayonet training so they might be more prepared in the event of running out of ammo in the middle of an engagement. Interviewed soldiers identified further deficiencies in their training, and wished for instruction on multiple infantry weapons rather than just their assigned weapon, as well as more training in night time and defensive actions. Interestingly, while Marshall claimed he was responsible for improvements in US Army training regimes between WWII and Korea, an alarming number of GIs signalled they were unhappy with their weapons training, which focused too heavily on offensive fire. Said one GI: “You’re never taught in basic that you can be shot at, too; you always just take a hill and are never run off it.”

Ultimately, Marshall was in Korea at the behest of the ORO, whose independent report owes much to Marshall’s informal method of gathering a few enlisted men and asking open ended questions. However, since the ORO’s object was to compile a quantitative report rather than compile oral accounts to construct a broad picture of a battle, historians and students alike will find in ‘Use of Infantry Weapons and Equipment in Korea’ a versatile and compelling window into the nature of infantry fighting in the Korean War.

Click here to read ‘Use of Infantry Weapons and Equipment in Korea’.

Additional Operational Research Office reports on ‘The Effects of Terrain on Battlefield Visibility’ and ‘Operational Requirements for an Infantry Hand Weapon’ can be found in the Ronnie Shephard Fonds.

Readers interested in learning more about S.L.A. Marshall and the ratio of fire controversy should see:

- “Right for the Wrong Reasons: S. L. A. Marshall and the Ratio of Fire in Korea” by Kelly C. Jordan in The Journal of Military History, Vol. 66, No. 1 (Jan., 2002), pp. 135-162.

- “S.L.A. Marshall and the Ratio of Fire” by Roger J. Spiller in The RUSI Journal Vol. 133 No. 4 (Winter 1988), pp 63-71.

- “S.L.A. Marshall and the Ratio of Fire: History, Interpretation, and the Canadian Experience” by Robert Engen in Canadian Military History, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Autumn 2001), pp. 39-48.

- “S.L.A. Marshall Revisited?” by Dave Grossman in Canadian Military Journal, Vol. 9, No. 4 (Winter 2009) pp. 112-113.

- “S.L.A. Marshall’s Men Against Fire: New Evidence Regarding Fire Ratios” by John Whiteclay Chambers II in Parameters Vol. 33 No. 3 (Autumn 2003), pp. 113-121.